Please note the date of this lament from a veteran participant in a multi-decade scheme to engineer western North America to accommodate a burgeoning population and vibrant economy:

“There it lay—the last frontier—an appeal to the mind of the few adventurous souls who might wish to penetrate its fastnesses and plunge for weeks beyond human communication.

“The Forest Service sounded the note of progress. It opened up the wilderness with roads and telephone lines, and airplane landing fields. It capped the mountain peaks with white-painted lookout houses, laced the ridges and streams with a network of trails and telephone lines, and poured in thousands of firefighters year after year in a vain attempt to control forest fires.

“Has all this effort and expenditure of millions of dollars added anything to human good? Is it possible that it was all a ghastly mistake like plowing up the good buffalo grass sod of the dry prairies? Has the country as it stands now as much human value as it had in the nineties when Major Fenn’s forest rangers first rode into it?” — from The Passing of the Lolo Trail, by Elers Koch [Journal of Forestry, Volume 33, Issue 2, February 1935, Pages 98–104]

Despite Elers Koch’s passionately stated doubts in 1935, the U. S. Forest Service’s ‘Great Fire’-inspired suppression policy— an effort to prevent all wildfires on forested lands or to extinguish them by 10 AM of the day following discovery of the blaze—continued apace into the 1970s, with the advancing knowledge of wildfire and forestry science eventually steering a slow, hesitant turn toward wildfire management and prescribed burns. By the the late 1980s, in a national forest district I was mapping for riparian habitat and endangered plants, I shared a forest work camp with a bunch of highly skilled fire crew pyros who were spending as much time that season lighting fires as fighting them. Evening porch talk centered on enthused discussions of torch and firebreak techniques, watersheds, fishing and the condition of the two-track roads we all depended upon to get us around the forest. I don’t recall Elers Koch’s philosophical laments edging their way into the conversations.

Water Into Stone’s last two essays explored the disruptive effects of human migrations, and unforeseen consequences of previous human efforts to engineer habitats. Today I’ll feature some current human efforts to understand and steer through the adventures and misadventures ahead of us all. Up first, a look at the ever-increasing acreage consumed by wildfires in recent years. A history of the 3-million acre Great Fire of 1910 says the burn area was about the size of Connecticut.

Here are some more recent comparatives:

1980s - an average of 2.7 million acres of U. S. public land burned per year (a bit smaller than Connecticut, if you’re counting)

2011 to 2020 - an average of 7.5 million acres per year (= the size of Hawaii)

2020 - over 10 million acres (= more than the combined acreage of Massachusetts and Connecticut)

In 2022, 7.6 million acres—another Hawaii-sized bite. In 2023, ‘only’ 2.5 million acres of U. S. public land has been burned by 46,681 fires so far, a comparatively mild year by recent averages, but here are a couple of comparatives from north of us in Canada:

2023: 45 million+ acres burned so far, more than double 1989’s total of 19 million acres, the previous worst fire year on record—“…the combined size of more than half the countries in the world,” says a New York Times story I’ll link to at the end of this essay.

These ever-rising totals are in the face of a multi-decade long acknowledgement among fire scientists of the folly of attempting to eliminate wildfires from forested lands, and a steadily-growing commitment in the last 50+ years among forest management agencies to use prescribed burns, forest thinning, and the application of ‘let it burn’ practices whenever possible, in an effort to cut fuel loads and protect wildland/urban/interface developments and investments. So, what has gone wrong? Here’s an excerpt from a recent article that, despite the usual dose of scientific notations, citations, and equivocations, helps explore this question:

“Although considered a widely applicable solution, there are many impediments to prescribed fire implementation30,31, including staffing and funding limitations, risk tolerance, and smoke impacts32). For these and other reasons, prescribed fires are not implemented during all suitable burn windows—suggesting that, to date, climate has not been the primary inhibitor to implementation and that present-day burn windows are often underutilized33,34,35. However, in recent years, the combined effects of severe short-term drought and long-term aridification16 have contributed to a reduction of adequate spring and autumn burn windows in some regions32,35, raising concerns that climate change will add to the many existing challenges to prescribed fire implementation36.” — from “Climate change is narrowing and shifting prescribed fire windows in western United States,” by Swain, D.L., Abatzoglou, J.T., Kolden, C. et al. [Communications Earth & Environment volume 4, Article number: 340 (2023)]

Below are two graphics from the paper that help break down the above jargon into a more easily digested form (Rx Days = suitable days for prescribed burns):

There are plenty of seasonal and climatological nuances in the full article, if you’d like a long read on some dark and stormy night, but casually parsing news headlines of recent fire seasons reveals that the reduction of safe burning windows has resulted in many delays, misjudgements, and some high-profile wildfires escaping their planned boundaries, a few with disastrous results—including one in northern New Mexico from 2022, when a long-smoldering mid-winter burn and an April prescribed fire escapee joined to become a 341,000 acre conflagration that destroyed over 900 structures, caused flooding during the summer rainy season, and shut down the U. S. National Forest Service’s prescribed burn program for six months. Wildfires traced to fallen power lines in California, Colorado, and Hawaii have sparked multi-billion settlements, or are still being adjudicated.

By recent evidence, and with the aridification of western North America proceeding faster than predictions, unless humans take vastly stronger actions to contain and reverse their entrenched habits of using ever more of the planet’s resources to ease and enrich their own species’ lives, these trends are likely going to get worse before they get better, so many academics, policy gurus, and an array of long-time residents and new arrivals to fire-prone landscapes are offering a somewhat dizzying array of engineered mitigations and habitat modification, with varying degrees of earnestness, experience, and expertise. Though many of these are obfuscated by real or imagined layers of property and/or treaty rights, jurisdictions, traditions, and grievances, from among the welter will come courses of action that will affect the living inhabitants of all continents, islands, and bodies of water. The techniques of the past must be modified to match the evermore crowded and climate-altered present and future, and the strident political fallout and massive financial liabilities of recent escaped wildfires should serve as warning to any individuals, groups and/or governmental entities that presume to claim autonomy in their actions.

In the interest of seeking collaborative approaches, here are two links that offer valuable ideas to consider:

Adapting Western US Forests to Climate Change & Wildfires is an interactive story map with various map and video links, and point by point Q & A about the nuanced relationship between forest thinning and prescribed burns, and the effect of planting more trees post-burns vs. maintaining healthy, existing forests with low-intensity fires and forest thinning.

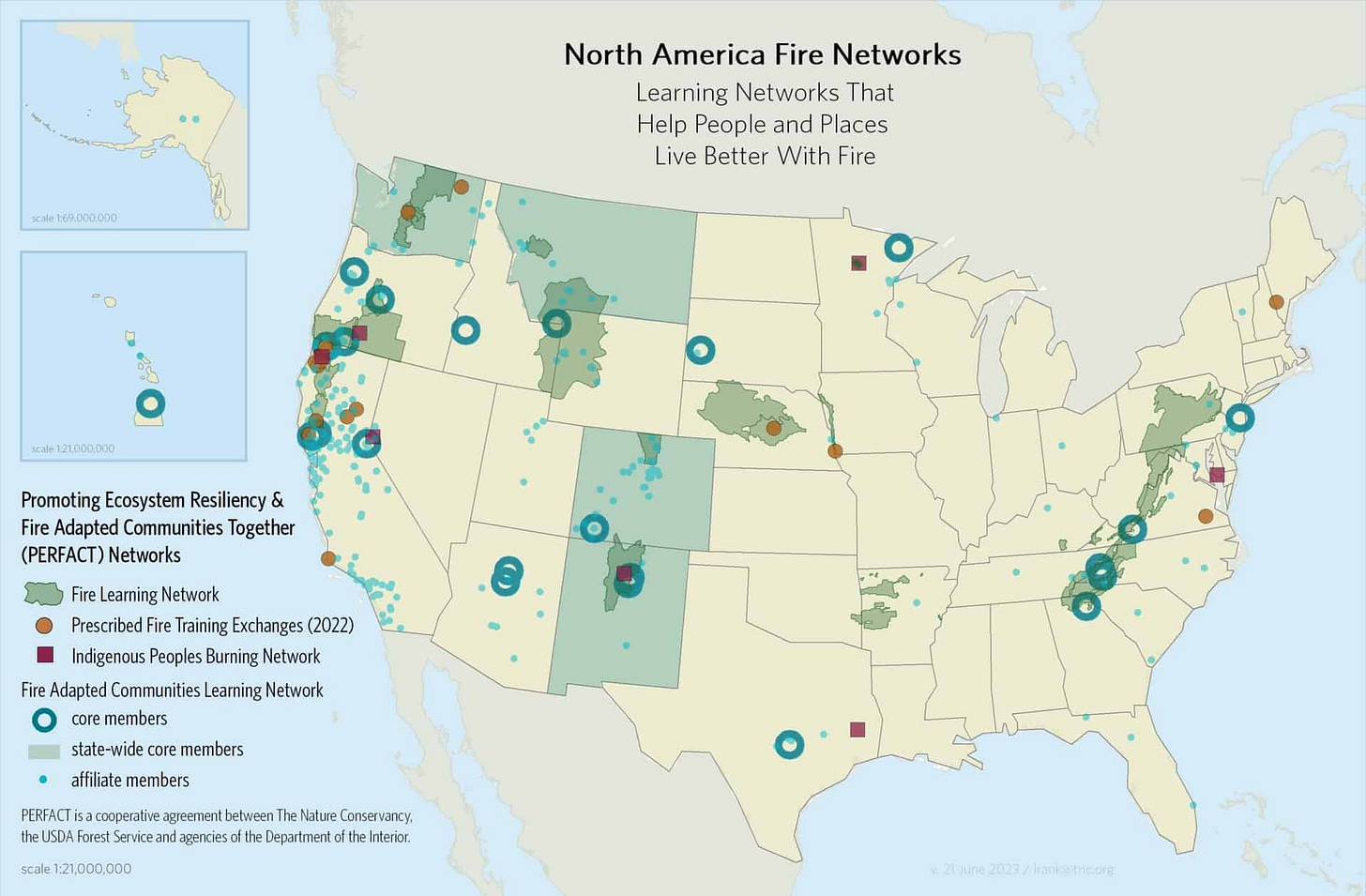

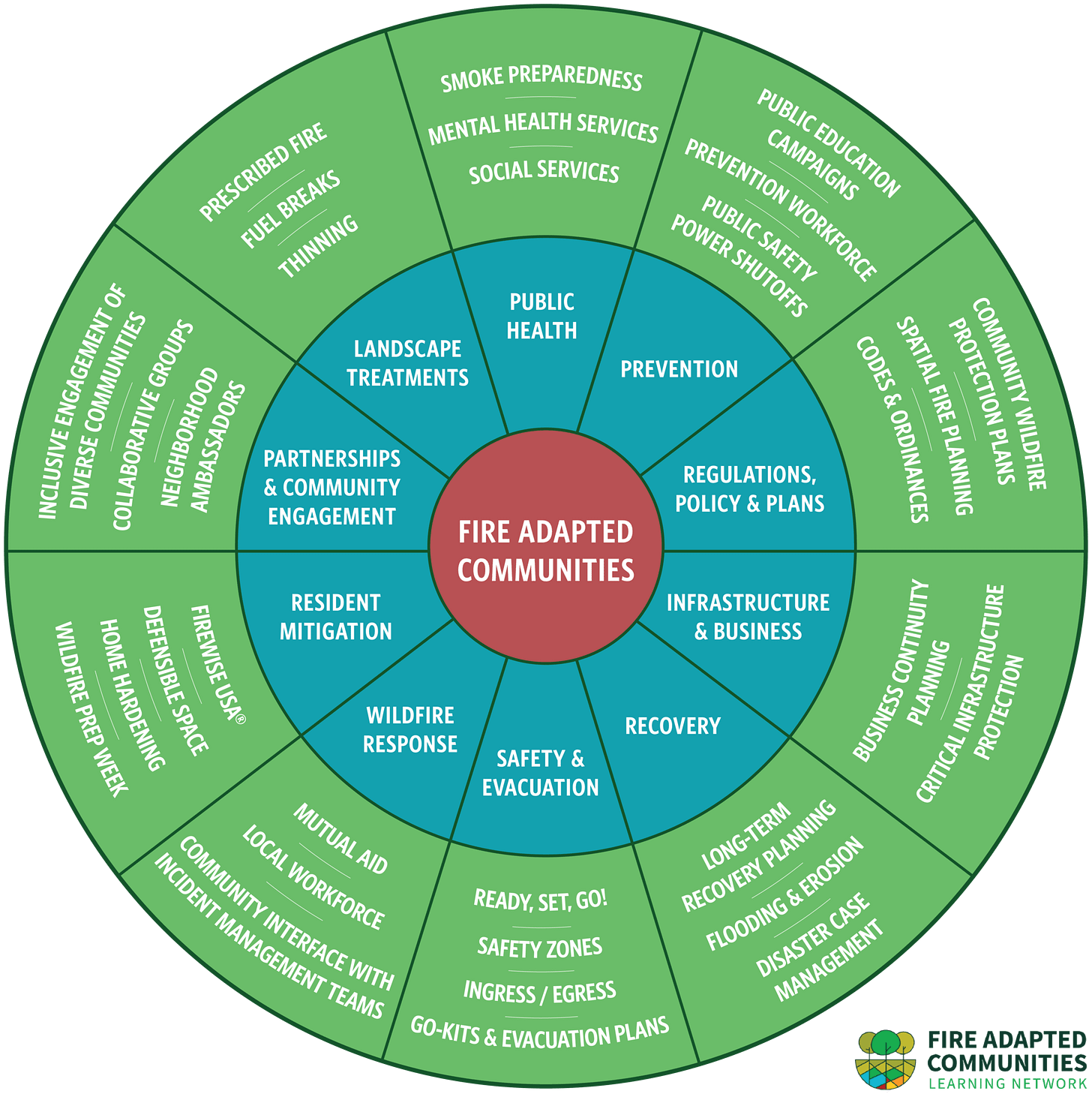

Fire Adapted Communities Learning Network (FAC Net) is a multi-organizational effort to support community-led attempts to mitigate and/or adapt to wildfire dangers across North America—offering workshops, webinars, trainings, and technical assistance to a range of wildfire resilience practitioners, non-governmental organizations and local governments, with a strong but not exclusive emphasis on indigenous participation and leadership. Here’s an impressive annual report of FAC Net projects from 2021. The chart below shows the range of ideas addressed:

…and here is a map of projects and collaborations from 2022:

I began life on a small Colorado sawmill in the midst of the Smokey Bear-branded era of defeating all wildfires, and at various points I’ve joined ad hoc fire brigades using shovels and axes to beat back advancing flames. I’ve also undertaken solo actions to extinguish lightning-caused spot fires, prescribed fire hot spots, smoldering abandoned campfires, and roadside blazes I’ve come across in my rambles. As a lifelong denizen of fire-prone landscapes, I am impressed by the above organizations’ efforts to inform and enlist, rather than exclude, the range of humans that—regardless of wealth, status, ethnicity, country of origin, and/or length of residency—now live, recreate, and rely on these lands. The earth long ago ran out of new continents for humans to explore and colonize, so rather than denying others the opportunity and means to pitch in, it seems wiser to offer shovels and fire-sticks, along with the knowledge, skills and means to responsibly use them.

Up next, Road Trip Pics—A Plateau’s Autumn Palette. Until then, let’s help each other enjoy our beautiful home planet. - B.

‘It’s Like Our Country Exploded’: Canada’s Year of Fire is a remarkable, long form story by The New York Times writer David Wallace-Wells about the devastation left by massive wildfires in Canada that records and honors the confusion, grief, stories, and often heroic efforts by affected Canadians caught on this year’s version of the front lines of climate and social catastrophe.

For an informative look at current cultural burning practices (aka fire-stick farming) in Australia, here is a well-produced video from Australia’s public broadcasting service, ABC:

Coming back into my Rocky Mountain home country, here is a Colorado Sun article about infusing mushroom mycelium into the forest duff and chipped wood debris left after fire mitigation logging and thinning projects, “Colorado’s latest tool to fight forest fires: Mushrooms.”

Excellent comparative summary, which gave me a more accurate historical perspective. I also enjoyed reading the Colorado Sun article, Colorado’s latest tool to fight forest fires: Mushrooms. This gives an exciting option in addition to forest fire management via tree thinning. I always like to hear new applications for the amazing properties of mycellium!

I loved this article. Not really related to forestry practices, but I spent a day or two fighting wild grass fires in Colorado back in the early seventies. My Army division on return from overseas, set up shop in Colorado and during downrange live fire exercises would routinely set the dry grass on fire (probably from the incendiary rounds in the mg fire.) We used wood poles with rubber flappers to beat the fires out if you can imagine that.. Fires in the woods were another thing and I got pulled into that too, but that's a story for another day.